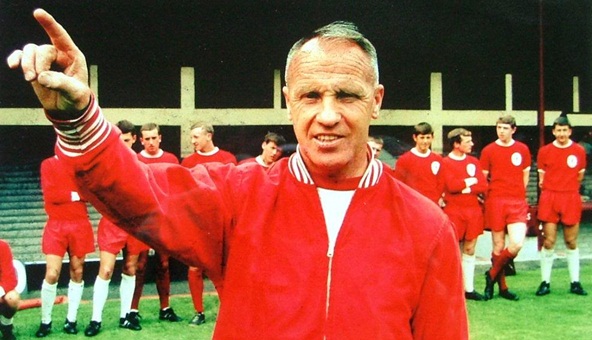

In 2006 David Peace wrote the outstanding The Damned Utd, which fictionalised Brian Clough’s calamitous 44-day reign at Leeds United. Now he brings his unique writing style to the legendary Bill Shankly in Red or Dead.

There are already many excellent books about Shankly, including The Real Bill Shankly, written by his granddaughter, Karen Gill. It may well be though that Peace has written the masterpiece, blending fact and fiction to create the ‘true’ Gospel According to Shankly. Peter Hooton, founder member of Spirit of Shankly Liverpool Supporters Union and one-time front man of Scouse indie hopefuls, The Farm, has proclaimed: “I want to go out and knock on doors like a Jehovah’s Witness and read this book to people.”

Peace’s book is an epic of more than 700 pages in two halves. The first deals with Shankly’s appointment by a largely unambitious board of directors, unaware that they’ve hired a revolutionary genius; his subsequent success at transforming a mediocre side from mid-table of the second division into league champions, and FA Cup winners for the first time in the club’s history; and in the fifteen years between 1959 and his shock resignation in the summer of 1974, to the cusp of European greatness. The latter, shorter ‘half’ deals with a Shankly bereft of the training-ground buzz at Melwood and the competitive arena of Anfield, and even apparently offered a footballing life-line by neighbours and rivals Everton. Shankly was a resident of the West Derby district of Liverpool, close to Everton’s then training ground, Bellefield. Although not necessarily short of work in this period he never returned to Anfield in the capacity he so desired. Political change in the late 70s also shook Shankly’s values, leaving him adrift as a sort of King Lear of Merseyside. The book certainly has an Homeric epic scale to it, and chronicles Shankly’s teams in more detail than ever before. Richard Lloyd Parry, writing in The Times, has said that it has “more in common with Beowulf or The Iliad than with the conventional sports novel”.

Some criticism has been levelled at Peace’s trademark repetition of words and short sentences to create a sense of rhythm: for example, “at home, at Anfield” is used frequently throughout. This technique was deployed to good effect in The Damned Utd, giving a sense of Clough’s paranoia but also capturing his hubris. It’s not to everybody’s taste, but it works effectively enough again here, taking on an almost poetic quality.

How Shankly’s mining background in East Ayrshire shaped his outlook and politics is an underlying theme, as he seeks to harness his vision of socialism via hard graft and the simplicity of team work. He also despised cheats and demanded honesty from his players and staff. Witness Shankly making a speech amongst thousands of Liverpool supporters in Williamson Square when they’d just lost the 1971 FA Cup Final to Arsenal. Professional politicians would envy such charisma and connection. “Since I’ve come here, to Liverpool, to Anfield, I’ve drummed it into our players, time and again, that they are privileged to play for you.” You hear so many managers today trade on similar bland platitudes about their players, but with Shankly it was delivered with such conviction and belief that it still inspires. This was the man, after all, who when he’d retired would regularly stand on the Kop to watch Liverpool and to be with his people. Regular Kopites would do a double-take in disbelief and would want to make sure that Shanks wasn’t pushed or shoved amongst the rowdy throng, but Shankly wouldn’t have any of it. This was the man who could be seen regularly in the mid to late 70s playing football on the playing fields opposite his house on a Saturday and Sunday (now officially renamed the Bill Shankly Playing Fields) with groups of children, directing them and encouraging them with all the energy and gusto he’d employed as manager of Liverpool FC. This was the man who, taking the acclaim of the Kop at the final whistle after Liverpool’s 0-0 draw with Leicester City at Anfield to capture the 1972-73 league championship, picked up a discarded scarf from the terrace which, having been casually kicked to one side by a police constable, lay on the perimeter dirt track, dusted it off and firmly tied it around his neck and then squarely confronted the copper in question, angrily repeating: “That’s someones life, that’s someone’s life!”

The politics of Shankly certainly had much in common with the likes of Clement Attlee and Harold Wilson, who was a guest on Shankly’s radio show on local Liverpool station, Radio City on 1 November 1975. The book contains genuine transcripts from this broadcast. The likes of Margaret Thatcher left him cold, and the fictionalised scene depicts Shankly contemplating his own mortality as the Tories sweep to victory in May 1979.

In a summer in which everything distasteful about the modern game has been exposed, be it star players trying to force through a transfer, disloyalty and the influence of money and agents, to inflated ticket prices and worldwide franchise pre-season club tours, this book provides the antidote to the money-obsessed Premier League era and harks back to the days when true titans in the shape of Shankly, Busby, Stein, Clough, Nicholson and, dare I say it, Ferguson strode the football landscape. It is how football was meant to be; it is how it should be now.